U.S. Government Debt and Deficits: Do They Matter?

- While the U.S. has a historically large and growing debt burden, we do not expect the issue to pose an immediate crisis for markets. Still, a large deficit can constrain other fiscal spending priorities and crowd out private capital, potentially hindering growth.

- The unsustainable trajectory for U.S. government debt may come into the spotlight in 2025, when federal lawmakers are expected to debate tax policy.

- In our view, the U.S. central bank and federal government have sufficient tools to address potential issues arising from the deteriorating fiscal situation. We also have means to adjust portfolios should we become concerned about the U.S. debt’s impact on markets.

The United States currently faces a deteriorating fiscal situation characterized by high and rising government debt, with no clear resolution in sight. The federal debt-to-GDP ratio of almost 100% is a peacetime high, and its climb is set to continue based on existing fiscal policies. While substantial deficit reduction is unlikely in the near term, we expect fiscal issues to come into greater focus once the election outcome and the policy priorities of the next administration are known.

Although the current U.S. debt trajectory is not sustainable, we believe an immediate crisis is unlikely. Several variables, including economic growth, productivity, government spending, and tax policy, have the potential to impact the path and ultimate impact of the current U.S. fiscal situation.

In this A Closer Look, we examine the factors driving the increase in U.S. government debt, the potential consequences of — and solutions to — having such a large deficit, and the investment implications associated with the growing national debt.

An Unprecedented Increase in U.S. Government Debt

The growing debt burden is a result of persistent federal deficits, which occur when expenses exceed revenue. The government funds the shortfall by issuing Treasury securities and bills at regular auctions. The federal deficit for 2024 alone is projected to be $1.8 trillion, contributing to a gross national debt that recently surpassed $35 trillion.

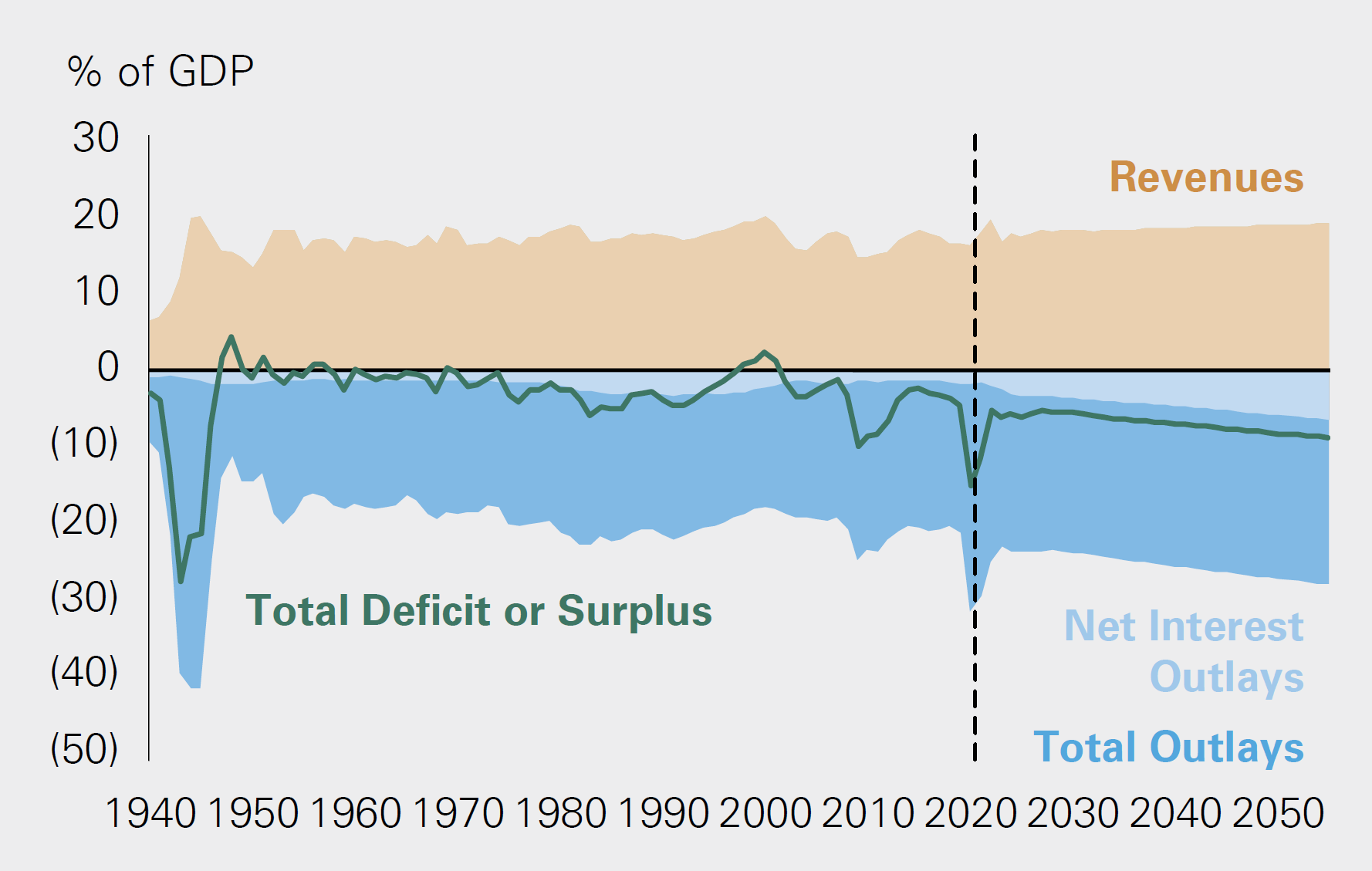

To put such a large number in context and allow for comparison across years and between countries, it is helpful to look at government debt and deficits as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP). The debt-to-GDP ratio (as measured by federal debt held by the public) currently hovers around 100%, only slightly below the peak of 106% reached during World War II (Exhibit 1).

Exhibit 1: Federal Debt Held by the Public as a Percentage of GDP

Key takeaway: U.S. government debt has reached its highest level since World War II.

Exhibit 1: Federal Debt Held by the Public as a Percentage of GDP

U.S. government debt has reached its highest level since World War II.

Driver of the Increase in U.S. Government Debt

The U.S. debt situation has deteriorated rapidly over the past two decades. The U.S. has seen its debt-to-GDP ratio more than triple since 2001, rising from 32% to approximately 100%.

The dramatic increase can be attributed both to rising expenditures as well as declining revenues relative to GDP. Since 2001, increased spending has accounted for two-thirds of the budget deficit growth, while falling revenue makes up the remaining third, according to the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget.

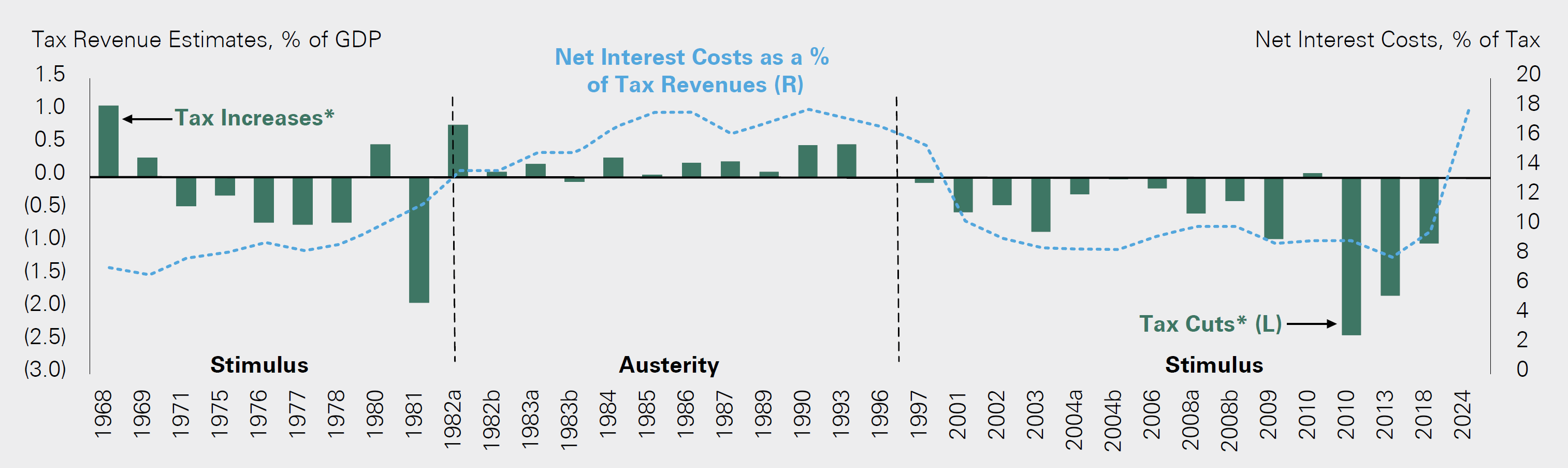

Even before the onset of COVID-19, the U.S. was deeply indebted, and the government’s response to the pandemic exacerbated the situation. Unusually high fiscal spending, including on pandemic-related and infrastructure initiatives, over the past few years has kept debt levels elevated. As expenditures have continued to exceed revenues, the federal government has relied on borrowing to cover the shortfall. The 2023 fiscal deficit was alarmingly high at 6% of GDP (Exhibit 2).

Exhibit 2: U.S. Government Revenues and Outlays as a Percent of GDP

Key takeaway: The U.S. deficit has risen in recent years and is estimated to increase further.

U.S. Debt Is Set to Increase Further

The core issue facing the U.S. is not just the absolute level of current debt but also the unsustainable trajectory of debt accumulation. Without significant policy changes, the federal debt-to-GDP ratio is expected to rise in the coming years, as government spending and interest expense continue to outpace revenue.

One key driver of the spending increase is demographic trends. The aging baby boomer cohort, combined with a longer life expectancy, is expected to drive up Social Security payments and healthcare costs. Neither taxes nor tariff revenues are expected to increase by a corresponding amount.

Indeed, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects that, if current laws governing revenues and spending remain unchanged, the U.S. national debt could top $56 trillion by 2034, and the debt-to-GDP ratio could reach 122% of GDP by 2034 and 166% by 2054 (Exhibit 1).

The Problems With a Large Deficit

Large and growing deficits pose several risks to the U.S. economy given their potential impact on economic growth and the growing cost of servicing the debt. As federal debt increases relative to GDP, a rising share of government revenues will be directed toward interest payments, taking share from other government spending priorities. Persistent deficits, and the resulting increase in government debt, can reduce real incomes by crowding out private investment, hindering job creation, and curbing productivity.

However, the nature of deficit spending matters. Spending that contributes to greater potential GDP growth may be more sustainable than spending that does not boost growth.

The CBO estimates that deficits will continually exceed potential GDP growth, leading to fiscal losses that outstrip economic gains, a dynamic typically seen only during economic crises. Additionally, the currently high debt-to-GDP ratio raises concerns that the debt situation could worsen if the economy falters, driving a need for additional fiscal stimulus.

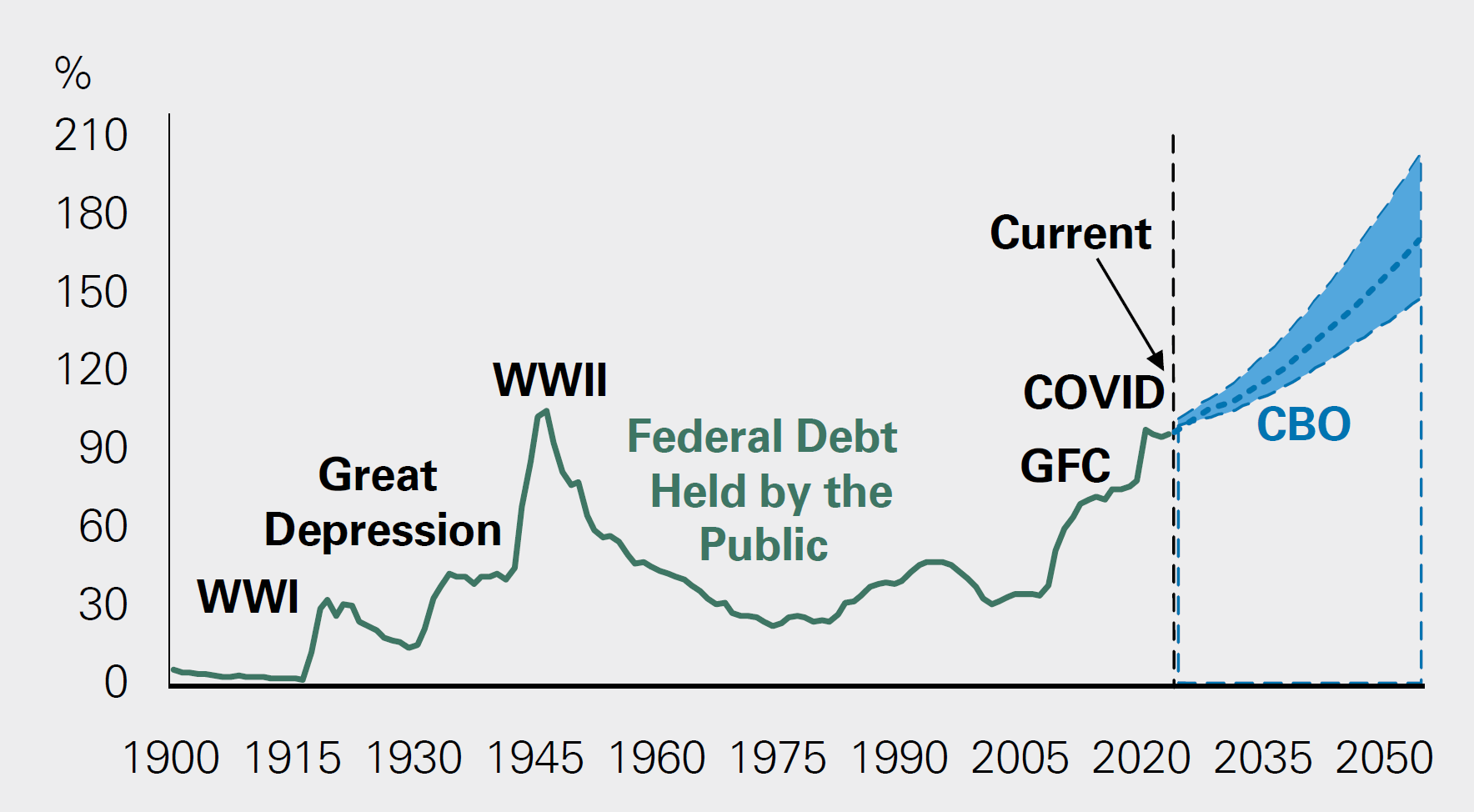

In 2023, the U.S. paid a record $658 billion in debt service. For the first time in history, the U.S. is spending more on debt interest payments than defense. Today, interest costs are already 18% of tax revenues and are expected to rise further.

Historically, when interest costs surpass 14% of tax revenues, the government has implemented fiscal austerity measures (Exhibit 3). In the 1980s and 1990s, when interest rates on federal debt became a burden, the government cut spending in other parts of the budget.

With interest rates currently higher than in recent years, the cost of servicing the debt is likely to increase, especially as a significant portion of the debt matures and needs to be refinanced. While the Federal Reserve is positioned to further lower interest rates after an aggressive hiking campaign, we do not envision rates returning to the lows of the prior decade.

Exhibit 3: Interest Costs and Fiscal Austerity or Stimulus

Key takeaway: Higher net interest costs have historically led to fiscal austerity.

Fixing the Deficit Problem

In our view, the main fiscal policy challenge is the large structural primary deficit. A primary deficit is the fiscal deficit excluding interest payments on prior borrowing. A structural deficit is a deficit that a country would have even if the economy were operating at its full potential (unlike a cyclical deficit, which can occur during a downturn in the business cycle).

The U.S.’s structural primary deficit currently stands at roughly 4% of GDP and is projected to remain elevated well into the future. While GDP growth may help offset the impact of higher interest costs on the debt-to-GDP ratio, the structural deficit is expected to keep adding to public debt.

Historically, large debt reductions have been achieved through a combination of sustained fiscal surplus, low interest rates relative to GDP growth, high inflation, or financial repression. For example, high inflation helped reduce debt following World War II; fiscal surpluses contributed to debt reduction in the late 1990s.

Presently, absent notably lower interest rates than the market expects, reaching a sustainable debt path is likely to require a material improvement in the primary balance driven by fiscal austerity (i.e., increasing tax revenues or slowing spending growth, potentially through reforms to entitlement programs). However, given the current political climate, this type of fiscal adjustment seems unlikely in the near term.

Lack of Political Will for Fiscal Austerity

There appears to be little political will to address the deficit. Both major political parties have shown a lack of focus on deficit reduction, with the leading presidential candidates calling for increased government spending.

- Republicans: While the GOP has proposed new tariffs to increase revenues, it also is proposing large tax cuts. The planned extension (or partial extension) of former President Trump’s 2017 individual and corporate tax cuts could add trillions to the deficit.

- Democrats: While a Democratic sweep of the presidency and both congressional houses might lead to tax increases, much of any additional revenue is expected to be used to fund new spending.

Without significant reforms to Social Security and Medicare, the biggest drivers of the national debt, substantial deficit reduction is unlikely in the near term. Absent external pressures, lawmakers are unlikely to address the deficit until forced, potentially in 2034 or 2036, when Medicare Part A and Social Security Trust funds are expected to be nearly exhausted.

Inflating the Way Out

With the political will to cut spending or substantially raise taxes lacking, inflation could become a tempting option for reducing the debt-to-GDP ratio. By printing money, the government could pay off its debt with cheaper currency, effectively reducing the real value of the debt.

However, this approach could lead to a decline in living standards, destabilize the economy, or potentially even put the U.S. reserve currency status at risk (see “U.S. Dollar Reserve Currency Status” below). Moreover, once markets begin pricing in higher inflation, interest costs likely would rise and negate the impact on the real value of debt.

While inflation might appear to provide temporary relief, it is not a sustainable solution and would likely lead to short- and long-term economic challenges. The recent spike in inflation is an all-too-recent reminder of the economic pain that makes inflation highly unpopular with the American public.

Productivity: A Silver Bullet

In the absence of fiscal austerity or inflation, the answer to the U.S. debt predicament could be increased productivity. Technological advancements, such as artificial intelligence (AI), have the potential to boost productivity and GDP growth, offsetting the impact of rising debt.

In the past, technological revolutions, such as the digital revolution, raised living standards through innovation. If there is one country in the world positioned to offset imprudent fiscal behavior with technological advancements, it is likely the U.S., given its innovative capabilities and deep capital markets.

Preliminary estimates of AI’s contribution to productivity growth improvements appear additive, though it is still too early to quantify exactly how strong the economic impacts may be. McKinsey estimates that generative AI could enhance labor productivity growth by 0.1% to 0.6% annually through 2040. However, these estimates depend on the speed of technology adoption and how workers reuse their time.

Compounding AI-driven productivity gains could drive meaningful improvement in long-term economic performance. While the impact on annual economic growth is likely to depend upon how productivity gains translate across sectors of the economy, the benefits of artificial intelligence could alter the U.S. debt trajectory toward the more favorable outcome in Exhibit 1.

Previously, improvements due to healthcare innovation (for example, generic drugs and cost-saving technologies) have prompted the CBO to lower its estimates for Medicare and Medicaid spending. Still, relying on future technological developments is risky. There is no guarantee that productivity gains will be sufficient to address the fiscal challenges facing the U.S.

Return of the Bond Vigilantes?

The limit to ballooning government debt is typically reached when debt servicing costs crowd out other critical spending — or when investors are no longer willing to purchase a country’s bonds at sustainable yields.

Some fear that a market event, such as the return of the “bond vigilantes” (fixed income traders who sell bonds or threaten to sell bonds to push back against the issuer’s policies), could ultimately force U.S. lawmakers to address the unsustainable structural challenges of the U.S. fiscal situation. Famously, during the 1990s, bond traders revolted against the Clinton administration’s large government spending and drove the 10-year yield from 5.2% in October 1993 to 8.0% in November 1994. In response, policymakers were forced to enact deficit reduction, and yields subsequently dropped.

We do not believe there is a meaningful risk of such vigilantism in the near term. However, concerns could resurface next year, after a new president is sworn into office and federal lawmakers’ negotiations over taxes have begun. Still, many investors already assume that the 2017 tax cuts will be extended, a difference from when the unfunded tax cuts of U.K. Prime Minister Truss took the market by surprise (see U.S. Government Debt and Developed Market Peers). If irresponsible tax cuts or government spending are proposed in either a blue wave or red wave scenario, outcomes we see as less likely than a divided government, it is possible a bond market reaction could provide a check on political plans. While we are watching closely for signs that a fiscal premium could be putting pressure on the long end of the curve, monetary policy, not fiscal policy, has been the bigger driver of yields.

U.S. Government Debt and Developed Market Peers

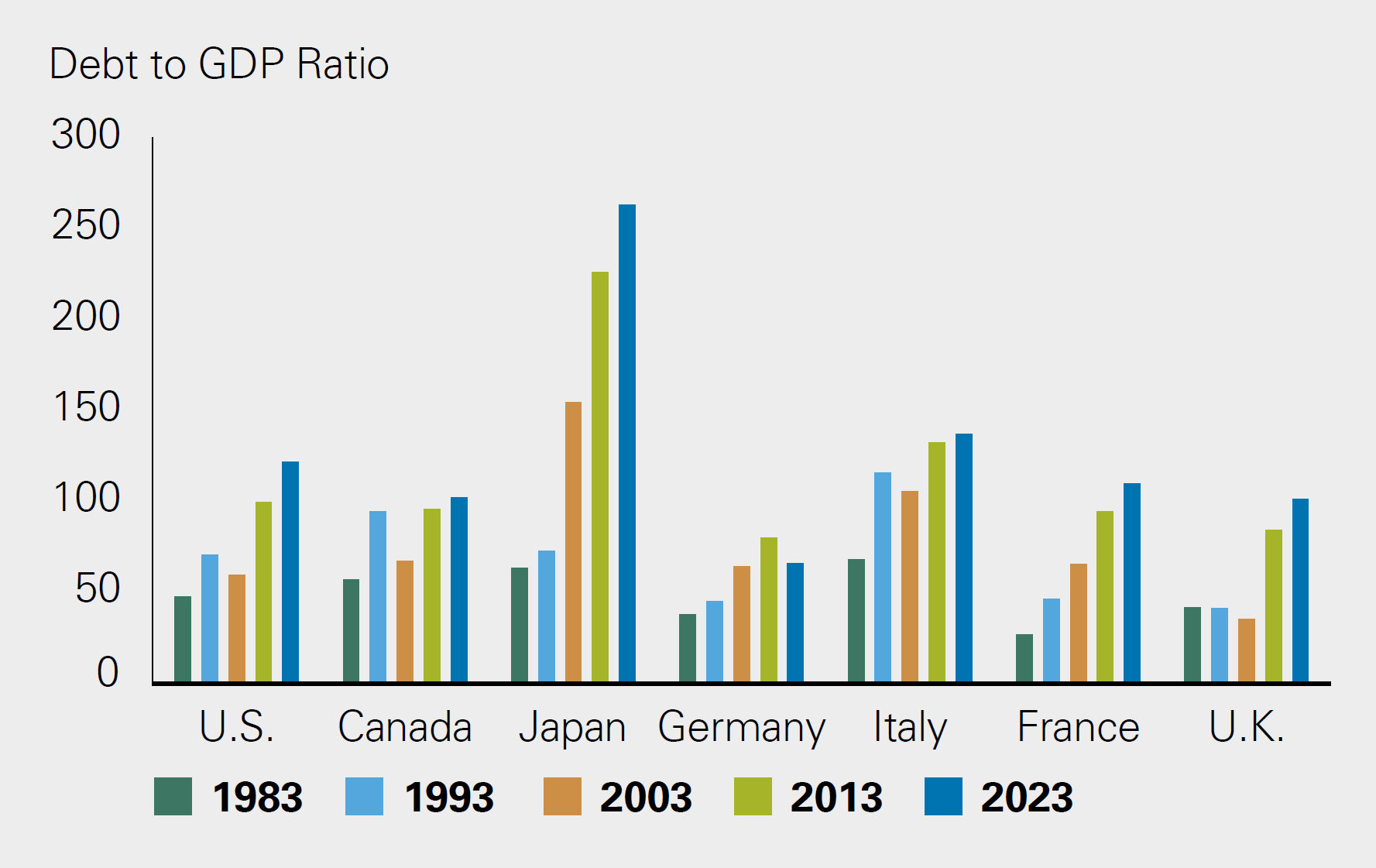

The U.S. is not alone in facing unsustainable government debt levels. Many developed economies are grappling with similar challenges. For example, France, Italy, and Japan all have high debt-to-GDP ratios and have struggled with fiscal deficits for decades (Exhibit 4).

France has some of the highest ratios of spending and tax revenue as shares of GDP. The country has not seen a budget surplus since 1974, at which time its debt-to-GDP ratio was below 20% (versus 110% today). Italy holds the record for the longest-running consecutive deficit — the last time it experienced a surplus was in 1925. For nearly 100 years, bondholders have funded the gap between tax revenue and spending.

Of its developed market peers, Japan has the largest debt-to-GDP ratio — surpassing 220%, more than twice that of the United States. Japan’s fiscal situation has deteriorated since its real estate and stock market bubble burst in the 1990s. In Japan, debt has been shifting from the private to the public sector for three decades: as the private sector has pulled back from borrowing, the Japanese government has stepped in, and public debt has increased.

Even though other countries are experiencing similar debt conditions as the U.S., this does not mean that large government debt burdens are not a problem; it simply means that the problem is not isolated to the U.S. Additionally, the debt trajectories of other countries show how these debt dynamics can last far longer than many initially expect.

Exhibit 4: Debt-to-GDP Ratio by Country

Key Takeaway: Among developed markets, the U.S. is not alone in carrying a large debt load.

Insights can be gained from how other countries managed their fiscal challenges through central bank intervention. European Central Bank (ECB) President Mario Draghi responded to the European debt crisis in 2012 with “whatever it takes” to prevent the financial risk premium on sovereign bonds from spiking. More recently, the Bank of England intervened to purchase long-term gilts in response to the Liz Truss crisis before the U.K. government was forced to withdraw its proposed budget.

If the U.S. were faced with similar fiscal challenges, we would expect policymakers could adopt a similar playbook.

Fed, Not Fiscal, Policy More Important in Driving Yields

Historically, bond markets have been driven more by monetary policy than fiscal concerns. While there have been times of worry, such as the Fitch downgrade to U.S. debt last year, we believe the U.S. economy and Fed policy will be the primary drivers of rates.

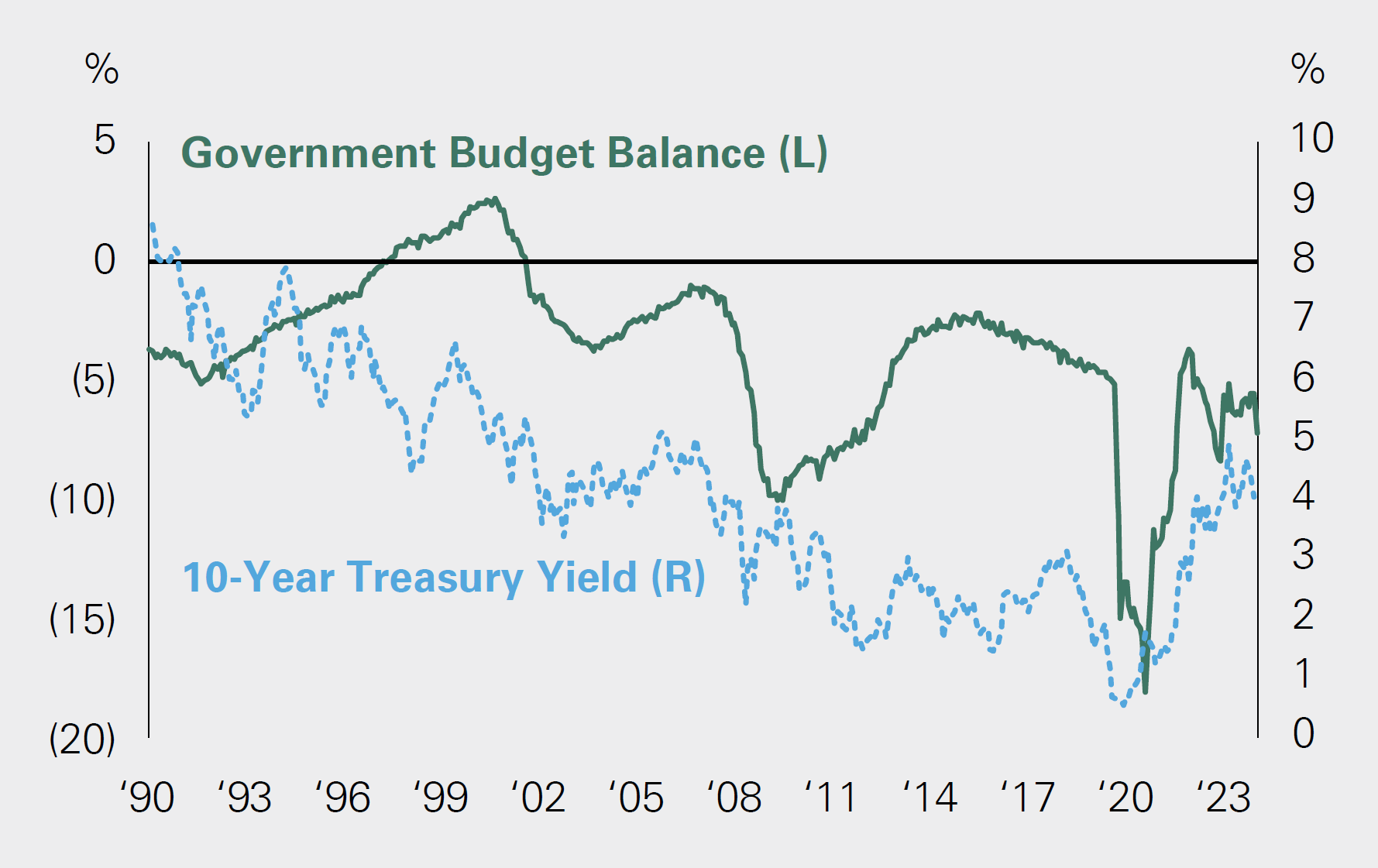

It is important to note that, historically, there has been almost no correlation between levels of budget deficit or public debt and levels of bond yields. On the contrary, since 2000, U.S. Treasury yields have been negatively correlated with U.S. government debt load: The bigger the deficit, the lower nominal and real rates have been (Exhibit 5).

Exhibit 5: Government Budget and 10-Year Yields

Key takeaway: U.S. Treasury yields have been negatively correlated with U.S. government debt load since 2000.

Exhibit 5: Government Budget and 10-Year Yields

U.S. Treasury yields have been negatively correlated with U.S. government debt load since 2000.

A Fiscal Crisis?

The probability of a U.S. default on its debt is virtually zero. As the U.S. is no longer on the gold standard, its fiat monetary system prevents bankruptcy. A nation cannot “run out of money” when it can print more, and its debt is denominated in its own currency.

During the gold standard era, several near defaults led to debt restructuring or suspension of interest payments. For example, in 1814, the U.S. suspended interest payments amid mounting war spending. During the Great Depression in 1933, FDR suspended the gold standard, prompting debt restructuring.

With the power of the printing press, a central bank can act as the buyer of last resort of government bonds. In essence, the central bank exchanges government debt obligations with its own currency by expanding its balance sheet, essentially removing the risk of sovereign default. Nonetheless, printing money without making structural changes is inflationary and unsustainable.

The Federal Reserve and U.S. Government Policy Response

If the U.S. faces a fiscal issue, both the Federal Reserve and the U.S. government have tools to address the problem. Should bond vigilantes shun Treasuries, the Fed could respond with major policy easing, including purchasing bonds through quantitative easing, similar to the central bank interventions seen in Europe and the U.K. (see “U.S. Government Debt and Developed Market Peers” on page 5). In fact, the Fed used a similar playbook in March 2020, after margin calls during the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic forced investors to sell bonds en masse, and the central bank stepped in to become the buyer of last resort.

In addition to the actions of a central bank, should markets come under pressure, we would likely see government action to bring down fiscal deficits, as we saw in the 1990s. If necessary, the government could also take more dramatic action, such as implementing fiscal austerity measures or capping interest rates, as it did at 2.5% following World War II, when debt-to-GDP reached a similar level.

Ultimately, it is important to remember that the U.S. fiscal problems are solvable. The central bank and federal government have ample tools to address potential issues arising from the U.S. fiscal situation.

In the short term, the central bank can act as the buyer of last resort to solve liquidity issues, and longer term, Congress can move to fix the fiscal picture if needed, albeit with the cost of pain through austerity or inflation if an unchecked deficit generates excess demand.

Investment Implications of Fiscal Issues

Given our investment style’s focus on quality, portfolio positioning is cognizant of potential fiscal risks. High quality companies are less subject to rate moves and bonds with solid credit quality are more insulated from fiscal issues.

Were we to become much more concerned about the market impact of the fiscal trajectory, we have several potential portfolio levers. We could allocate to short-term bonds or investment grade corporate securities, highly rated bonds from other developed economies, real assets, gold or other precious metals, or foreign currencies.

However, we don’t expect to be in this position. The U.S. government has tools to deal with a fiscally driven market crisis should one arise, and we believe it is important to remain invested today despite fiscal risks.

U.S. Debt Situation Not Likely an Imminent Threat to Markets

The U.S. faces challenges in managing its growing debt burden, especially given the exit from the ultra-low interest rate environment of the prior decade. In our view, the U.S. debt situation is unlikely to pose an immediate problem for markets, particularly as the Federal Reserve is easing policy, and demand for U.S. Treasuries should persist given the U.S. dollar’s safe-haven status (see “U.S. Dollar Reserve Currency Status” below).

While the U.S. may be able to navigate through a challenging fiscal situation for longer than many expect, we are closely watching Treasury auctions for any signs that a fiscal premium is driving an increase in longer-term interest rates.

We also remain mindful that the fiscal picture may return to the spotlight in 2025 amid the debate surrounding the expiration of the 2017 tax legislation. We have several portfolio options should we become concerned about the fiscal impact on markets, but we also believe it is important to remember that doomsday predictions have rarely turned out as feared.

U.S. Dollar Reserve Currency Status

One of the reasons the U.S. has been able to sustain its large deficit is the U.S. dollar’s role as the world’s reserve currency.

A reserve currency is a foreign currency that central banks hold as foreign exchange reserves, often in the form of government bonds such as U.S. Treasuries. The dollar’s dominance in global trade and finance creates consistent demand for U.S. dollars and Treasury bonds.

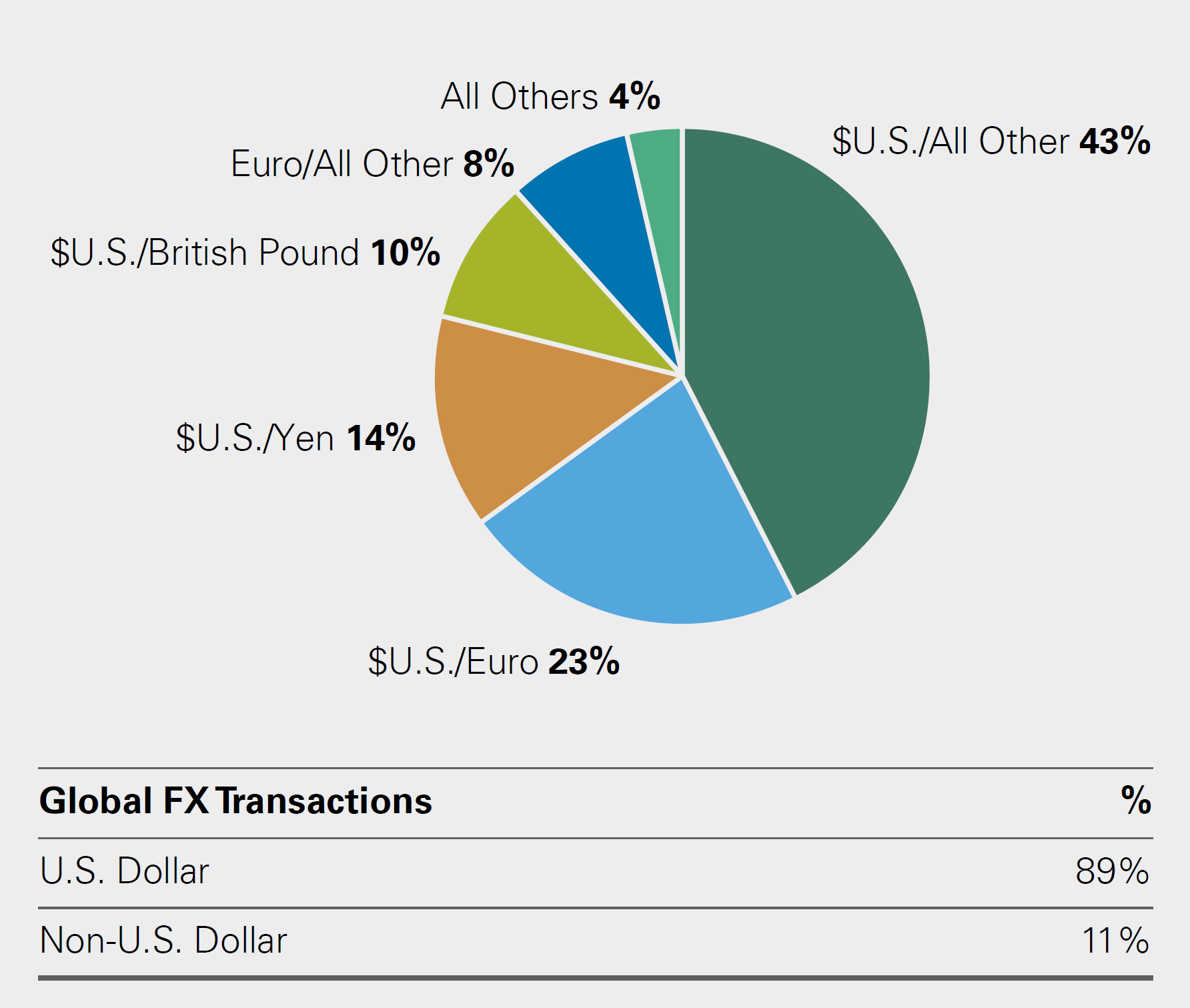

Countries maintain reserves for many reasons, including to pay for imports or service debts, to navigate economic shocks, or to adjust the value of their own currency. While the U.S. share of global trade is roughly 12%, the dollar dominates trade invoicing, foreign exchange, and debt issuance. Half of global trade and 90% of foreign exchange transactions involve the dollar, which also backs a significant share of cross-border loans and international debt securities (Exhibit 6).

Exhibit 6: Foreign Exchange Transactions

Key Takeaway: The U.S. dollar is involved in 90% of foreign exchange transactions.

Concerns of De-Dollarization

The sustainability of the dollar’s reserve currency status has been the subject of increasing debate due to shifts in global geopolitics, economics, and technological advancements. However, concerns about de-dollarization are not new, as highlighted in our 2021 Quarterly Investment Perspective, “The Future of Money.”

The formation of the euro, the growth of China, and the rise of Bitcoin all at some point contributed to fears the U.S. dollar would lose its coveted status. Most recently, the use of economic sanctions on Russia sparked such fears. The 2022 U.S. sanctions against Russia, which cut off its reserves and access to Western currencies, prompted Russia to sell U.S. Treasuries. While selling en masse has not been seen elsewhere, the increased use of financial sanctions could incentivize central banks to shift reserve portfolios away from currencies that are at risk of being frozen and motivate other countries to trade in other non-dollar currencies.

We acknowledge that geopolitical shocks or the overuse of economic sanctions could accelerate the trend toward de-dollarized trade and reduce the dollar’s influence over time. Still, several factors strongly support the U.S. dollar’s ongoing role as the world’s reserve currency: the U.S.’s strong alliance system, the naval and cyber supremacy backing the currency, and the lack of a credible alternative.

U.S. Alliance System

The U.S.’s extensive network of alliances across Europe, Asia, and Latin America plays a crucial role in maintaining the dollar’s reserve currency status, as countries with strong economic and security ties to the U.S. are more likely to hold U.S. dollar reserves. The influence of this extensive alliance system surpasses that of China, the U.S.’s most significant geopolitical and economic competitor.

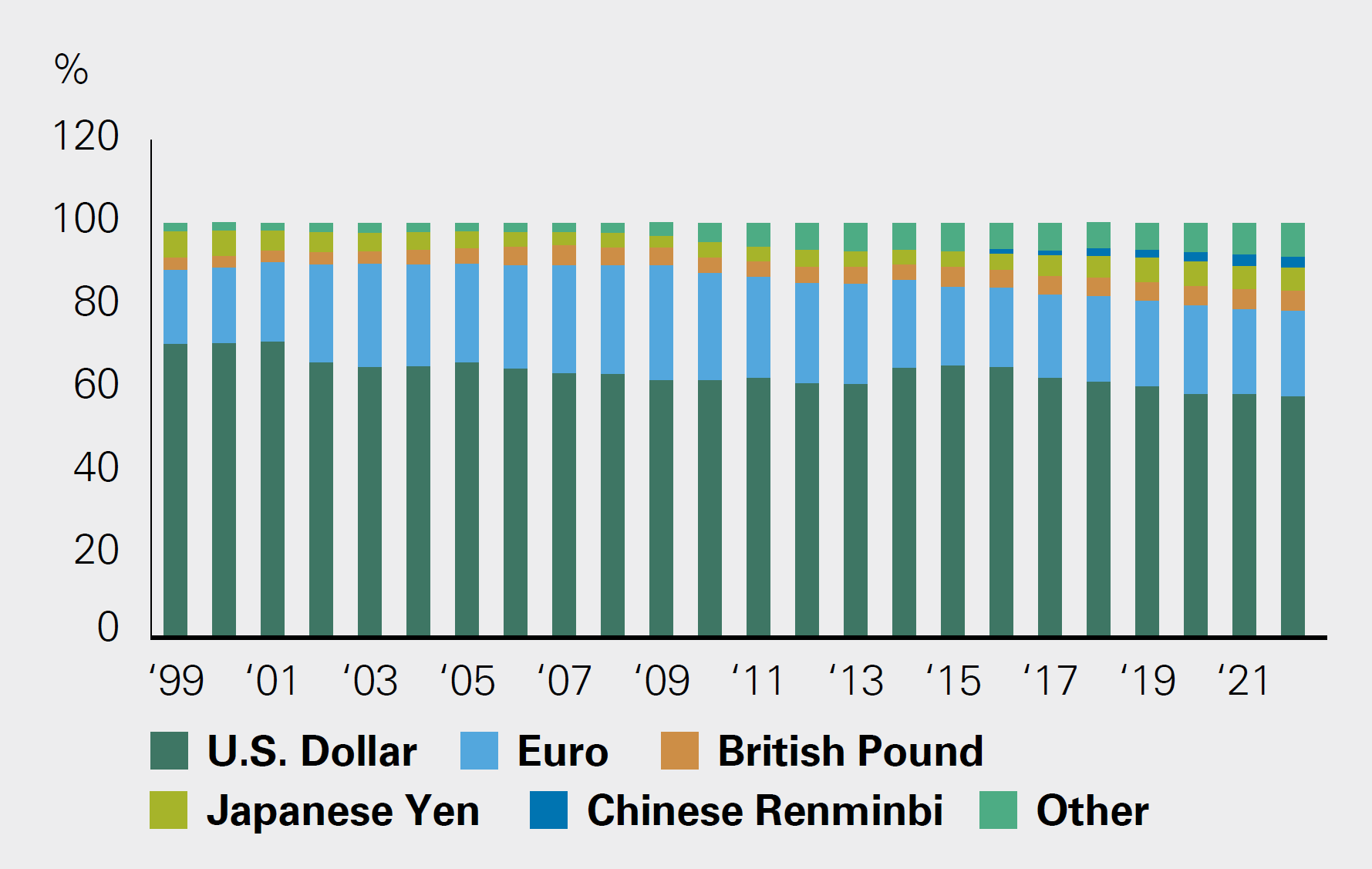

As of 2023, the U.S. dollar comprised about 60% of global foreign exchange reserves. While that figure is down from 70% in 2000, the decline mainly shifted toward currencies of U.S. allies (such as the euro, Japanese yen, and British pound) in addition to non-traditional reserve currencies (such as the Australian dollar, Canadian dollar, and South Korean won) (Exhibit 7). These nations, while offering alternative currencies, remain reliant on U.S. security guarantees, reinforcing the dollar’s dominance.

Exhibit 7: Share of Globally Disclosed Foreign Exchange Reserves

Key Takeaway: The U.S. dollar accounts for roughly 60% of global foreign exchange reserves.

U.S. Naval, Air, and Cyber Supremacy

Historically, dominant reserve currencies have been tied to the leading naval powers, whose control of trade routes shaped the flow of goods and global finance. Today, this principle extends beyond just naval dominance to include air power, telecommunications, and cybersecurity. The U.S. controls key global trade routes and maintains a powerful global military presence, uniquely positioning it to back the dollar with unmatched security. U.S. supremacy in cyber defense further supports the infrastructure of the global financial system. While China has expanded its naval and cyber capabilities, it remains far from challenging U.S. dominance, which supports the dollar’s continued role as the global reserve currency.

Lack of a Credible Alternative

Though there are growing concerns about the U.S. dollar’s future, no credible alternative has emerged to displace the U.S. dollar as the world’s reserve currency. Several potential contenders exist, but each faces significant limitations:

- China’s renminbi (RMB): Despite rapid economic growth, China has not internationalized its currency, the RMB. There is more to reserve currency dominance status than just size — market depth, liquidity, and the rule of law are also key. China’s currency is heavily regulated, with strict capital controls and limited liquidity in global markets. Its use in global trade remains limited, largely driven by China’s cross-border transactions rather than broader international adoption.

Indeed, the RMB’s share of global payments stood at only 2.5% in May 2023. While China has established currency swap lines and mechanisms to bypass Western financial systems, the RMB is unlikely to supplant the U.S. dollar anytime soon. Most countries want to hold their reserves in a currency with large and open financial markets to ensure they can access their reserves in a moment of need. - BRICS currency: The BRICS countries — Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa — have proposed the idea of a joint reserve currency to challenge the U.S. dollar. However, this effort faces significant obstacles. The vastly different economic structures and political systems within the BRICS nations would make coordinating a unified currency system difficult. Recent U.S. sanctions on Russia add another obstacle to the joint currency initiative. Finally, the imbalance of power, particularly with China’s much larger economy, would create tensions, making other BRICS members reluctant to depend on a Chinese-dominated currency system.

- The euro: Often viewed as the most viable alternative to the USD is the euro, which meets many of the economic criteria necessary for a reserve currency. However, the eurozone faces significant internal challenges, including fragmented debt markets and military power that currently fails to rival the U.S. In addition, the deep liquidity of U.S. Treasury markets far surpasses that of any European sovereign bond market, making the U.S. dollar more attractive for global reserves.

- Gold and Bitcoin: Often discussed as alternatives to fiat currencies, gold and cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin are unlikely to replace the USD as the global reserve currency. Some countries, especially those at risk of U.S. sanctions, have increasingly turned to gold as a hedge. However, gold’s physical limitations and Bitcoin’s volatility and lack of government backing prevent them from functioning as a stable reserve currency in today’s global financial system.

Reserve Currencies Are Lost Over Decades, Not Years

Finally, it is important to remember that reserve currency status is not lost in the blink of an eye. Historically, the fall of reserve currencies has been a slow, gradual process, often taking decades or even centuries. Since 1450, there have been roughly six dominant currencies. When the USD replaced the British pound as the global reserve currency in the mid-20th century, the U.S. economy was four times larger than the U.K.’s at the time.

Today, the stickiness of the U.S. dollar — its entrenched position in global trade, finance, and investments — is likely to make any significant decline a protracted process. The trust built into the U.S. financial system and the rule of law provides a level of stability and predictability that is hard to replicate. So, although the dollar’s dominance has slightly eroded in recent decades, substantial change is unlikely in the near term.

Still, we closely monitor the ability of the U.S. to maintain its global military and economic influence as it pertains to the dollar’s privileged status.

This material is for your general information. It does not take into account the particular investment objectives, financial situation, or needs of individual clients. This material is based upon information obtained from various sources that Bessemer Trust believes to be reliable, but Bessemer makes no representation or warranty with respect to the accuracy or completeness of such information. The views expressed herein do not constitute legal or tax advice; are current only as of the date indicated; and are subject to change without notice. Forecasts may not be realized due to a variety of factors, including changes in economic growth, corporate profitability, geopolitical conditions, and inflation. Bessemer Trust or its clients may have investments in the securities discussed herein, and this material does not constitute an investment recommendation by Bessemer Trust or an offering of such securities, and our view of these holdings may change at any time based on stock price movements, new research conclusions, or changes in risk preference.