How Big Is the Window to Transfer Your Wealth?

- Although the lifetime gift and estate tax exclusion amount is scheduled to drop from about $14 million per person in 2025 to about $7 million on January 1, 2026, the Republican sweep in November’s elections suggests the higher exclusion amount will be extended beyond 2026.

- This reprieve, however, is likely to be relatively short-lived. Due to legislative procedural issues and concerns about the U.S. budget deficit, we believe the higher exclusion amount will be extended for 10 years at most and, more likely, extended for two to five years.

- Clients positioned to make large gifts comfortably may wish to do so as soon as possible during their lifetimes, as they may save substantially on estate taxes by removing from their estates any future appreciation on those assets.

- Others who decide to delay making large gifts should still consider doing the planning now so they are ready to act if it becomes clear that the extension will be limited.

- Familiarizing yourself with the variety of estate planning strategies available can help you decide what is best for you and your family. Your Bessemer client advisor can help you assess how much you might transfer comfortably during your lifetime.

How much you can transfer free of estate and gift taxes is scheduled to be cut roughly in half starting in 2026: from $13.61 million in 2024 and about $14 million in 2025 to about $7 million in 2026 (including all adjustments for inflation).1

However, federal lawmakers can preserve the larger exclusion amount. And Republicans — who will soon take control of the government — have vowed to save the tax breaks in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, which includes this more generous exclusion amount.

Any extension they adopt is unlikely to be permanent, in our view. Given the Republicans’ slim majority in Congress, tax legislation is likely to be adopted using the reconciliation process. While new law requires 60 percent of the Senate’s vote to pass, budget reconciliation votes need only a slim majority (51 percent).

The rub is that the reconciliation process also imposes significant restrictions, including this: Tax cuts cannot be extended beyond a “budget window” (typically 10 years) — unless they are offset by other sources of revenue or spending cuts. Indeed, many pundits believe all of President Trump’s upcoming tax cuts will be extended for only two to five years due to deficit concerns.

The nation’s debt is $36 trillion today — up from $4.6 trillion in 2005 and $13.1 trillion in 2015. Even without any extension of the tax cuts, the federal government is expected to borrow roughly $22 trillion over the next 10 years.

Extending all the provisions in the 2017 Tax Act for 10 years would add an estimated $4.6 trillion to the deficit. Included in that number is $189 billion for extending the gift and estate exclusion amount for 10 years.

Planning Implications

Individuals with net worths of more than $7 million (or couples with more than $14 million) should consider making gifts that use the larger exclusion amount before it has a chance to decrease from about $14 million to about $7 million in as soon as two to five years. You could transfer as much as an extra $7 million free of the 40% estate and gift tax.2 (See “Significant Tax Savings May Be Had.”)

Others who are uncomfortable making large gifts might want to wait before taking the leap. But even they would be well-advised to start understanding their options and initiate planning. The window of opportunity to transfer more wealth free of estate and gift taxes appears to be bigger now than before the election, but it is likely still finite.

For those comfortable making large gifts, transferring wealth during the owner’s lifetime can be significantly more advantageous. And the sooner you make that transfer, the more advantageous it is likely to be, as future income from, and appreciation in the gifted assets will be removed from your estate.

As a starting point, your Bessemer advisor can help you determine how much you may need to fund your lifestyle and guide you through planning alternatives. (See “Your 10-Step Guide to Using the Exclusion Amount.”)

If you want to make use of the large exclusion amount while it is still available, we recommend contacting your estate planning professionals now so that you have ample time to make thoughtful planning decisions.

Given that such sizable gifts are usually made to trusts, it is important to have the time to carefully consider decisions such as which assets to use and what the terms of the trust should be.

Remember, you could do the necessary planning now (e.g., create the structure and select the assets) — then wait to see if the exclusion amount will be reduced and act only if the exclusion amount is reduced.

Bottom line: Be familiar with all your options, so you can make decisions that best suit your family. To that end, we provide this overview.

Significant Tax Savings May Be Had

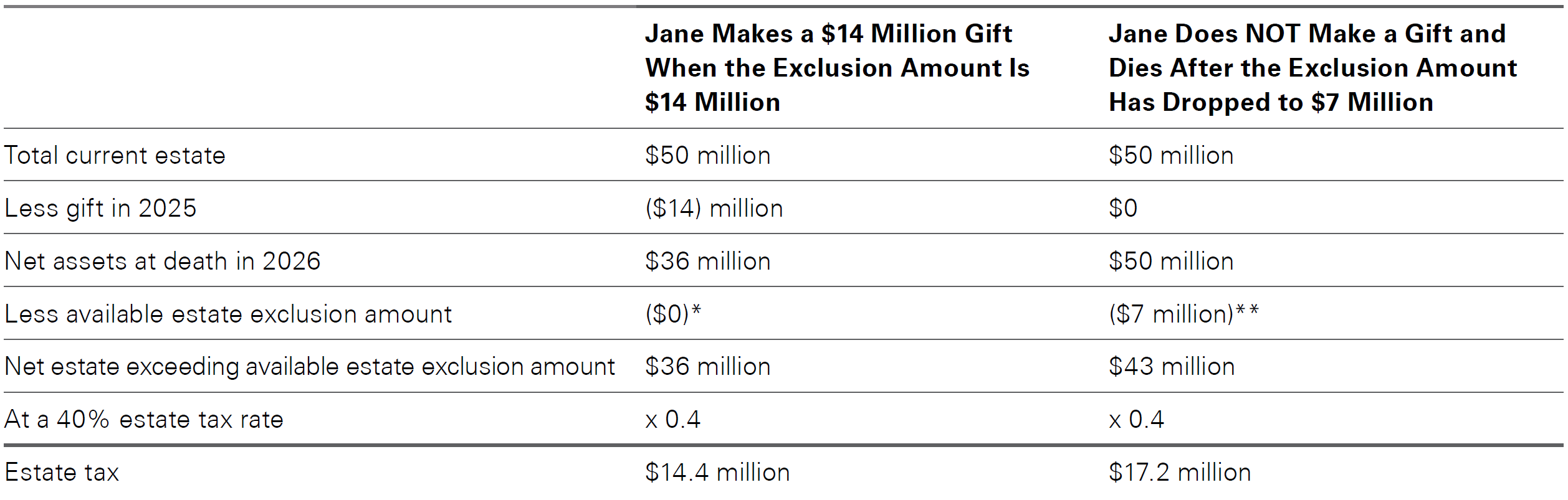

How beneficial is it to transfer wealth free of the 40% gift and estate tax?

Here is a simplified example of tax savings if you act before the exclusion amount is halved.

Let’s assume that:

- Jane has $50 million of assets

- She has not used any of her lifetime exclusion amount

- The current gift/estate exclusion amount is $14 million

- The gift/estate exclusion amount is reduced to $7 million before Jane dies

Consider the effects of Jane taking advantage of the window of opportunity by making a gift prior to the reduction of the exclusion amount:

By making the gift before the exclusion amount is reduced, Jane saved $2.8 million of estate tax ($17.2 million minus $14.4 million, see Exhibit 1). Another way of looking at it — Jane transferred an additional $7 million free of gift or estate tax, resulting in a savings of $2.8 million ($7 million x 0.4).

But the potential savings are actually much greater.

If Jane lives another 30 years and the “extra” $7 million of assets doubles every 10 years with income and appreciation, the $7 million would have grown to an additional $56 million in her estate. That is because it would double three times: to $14 million in 10 years, to $28 million in 20 years, and to $56 million in 30 years, resulting in an additional $22.4 million of estate tax (at a 40% rate).

This same advantage applies to the entire $14 million gift.

Of course, for married couples, the potential savings could be as much as $112 million in 30 years, if both spouses used their “bonus exclusion amounts” before the exclusion amount is reduced.

Significant tax savings are still to be had — even if the exclusion amount is not reduced.

If the individual makes a $14 million gift currently, the future income and appreciation from the gift is exempt from estate tax. If the individual lives another 30 years, the $14 million would have grown to $112 million assuming it doubles every 10 years, saving an additional $44.8 million of estate tax (at a 40% rate).

Exhibit 1: Failing to Take Advantage of the Higher Exclusion Amount Would Cost This Family Nearly $3 Million More in Taxes

Exhibit 1: Failing to Take Advantage of the Higher Exclusion Amount Would Cost This Family Nearly $3 Million More in Taxes

* The $7 million estate exclusion amount at death is less than the $14 million gift exclusion amount Jane used during her lifetime, so she has no exclusion amount left. (She does not have to “claw back” the “extra” $7 million; she just does not have any additional estate exclusion amount available at death.)

** The estate exclusion amount has been reduced to $7 million. It is all available to Jane because she did not use any of her lifetime exclusion amount with lifetime gifts.

** The estate exclusion amount has been reduced to $7 million. It is all available to Jane because she did not use any of her lifetime exclusion amount with lifetime gifts.

Special Planning Considerations for Married Couples

Married couples thinking of making significant gifts might want to discuss these key strategies with their estate planning professionals:

- Split Gifts — While both spouses might want to make use of their exclusion amounts before they may decrease, one spouse might not have $14 million of assets. Two planning alternatives may help.

First, if neither spouse has used much or any of his/her exclusion amount, one spouse could make a gift of about $28 million. Then, both spouses could make a so-called “split gift” election that, for federal gift tax purposes, would treat the gift as having been made equally by both spouses. Note, though, that this approach does not work efficiently if one spouse has previously used much of his or her exclusion amount.

For example: Assume that one spouse has previously used $10 million of his/her exclusion amount with prior gifts. A current gift of $28 million with a split gift election would treat each spouse as having made an additional $14 million gift. But, as this spouse has only $4 million of his/her exclusion amount remaining (again assuming for simplicity’s sake that the exclusion amount is $14 million), he/she would be making a $10 million gift over his/her available exclusion amount. That extra $10 million would be subject to a 40% gift tax.

This alternative also does not work if one spouse will be the beneficiary of the trust to which the gift is made (such as the SLAT discussed below). A spouse cannot split gifts to a trust of which that spouse is the beneficiary. - Ownership Changes — A second approach is possible if one spouse has a significantly larger percentage of the assets than the other spouse. The couple might re-allocate the assets so that each spouse can take advantage of the bonus exclusion amount. Such a reallocation must be done carefully, as these changes could result in a significant shift of marital assets between spouses. Be sure to consult your estate planning and tax advisors.

- Spousal Lifetime Access Trust (SLAT) Planning — Spouses might be reluctant to make a $14 million gift out of fear that they might need some of those assets for living expenses later.

A potential solution might be for one spouse to give his/her assets to a trust of which the other spouse is (or later becomes) a discretionary beneficiary. Distributions to the beneficiary-spouse might never be needed. However, if a financial reversal occurs, the trustee would have discretion to make distributions to the remaining spouse, which could be used to pay living expenses.

Note, though, that the SLAT technique has some risk. For example: What if the beneficiary-spouse should die before the donor-spouse? You could discuss with your attorney whether the beneficiary-spouse could be given a “power of appointment,” exercisable at his or her death, broad enough to allow appointing the assets to a trust in which the original donor-spouse is a discretionary beneficiary.

What if the beneficiary-spouse and donor-spouse get divorced? The trust can include provisions that dictate what happens in the event of a divorce.

Two Cautions

Use the full amount now — or (potentially) lose it.

If you make a gift of $7 million and the exclusion amount later drops to $7 million, you will have no unused amount left to give. You will be treated as having used your full (then $7 million) lifetime gift and estate tax exclusion amount.

Therefore, to use the large exclusion amount available now in case it is later reduced, an individual must gift the full exclusion amount. If using the full $14 million is not possible, there is still a benefit to using any of the “bonus exclusion amount” above the $7 million threshold.

Consider ensuring your estate has sufficient liquidity.

If the exclusion amount is decreased, many more decedents will be subject to the estate tax. For example, if the exclusion amount decreases to $7 million, a decedent with $14 million of assets who dies after the drop in the exclusion amount without having made any gifts to utilize the bonus exclusion amount, would owe federal estate tax of about $2.8 million ([$14 million – $7 million exclusion amount] x 0.4 = $2.8 million).

The federal estate tax is due nine months after the date of death, although extensions are available in some situations. Individuals with substantial illiquid assets (such as an interest in a closely held business or real estate) may need to consider the additional liquidity that will be needed to pay estate taxes if the exclusion amount declines at some point.

One solution is to acquire life insurance to provide the liquidity. In that case, the individual might consider funding a trust (specifically, an irrevocable life insurance trust or ILIT) to acquire the insurance so the insurance proceeds remain outside of the individual’s estate and are not subject to additional estate tax.

To be sure, if the exclusion amount is not decreased, the individual might have paid for life insurance that was not needed to pay estate tax. To minimize the risk of paying for insurance that might be unnecessary, consider establishing the ILIT and completing medical underwriting for the insurance but not binding the insurance until a later date, when the amount of the exclusion is clearer.

Your 10-Step Guide to Using the Exclusion Amount

Here’s how you might start exploring whether, and how, to use your full exclusion amount while it is still so robust:

- Make sure you will keep enough assets for your lifestyle needs.

The first step in any transfer planning is to ask your Bessemer advisor for financial modeling to help you assess whether you will have enough assets to provide comfortably for your lifestyle needs. - Use trusts.

Trusts are often used for large gifts — and with good reason — as they provide many protections. The trustee you choose should be someone you know will manage the assets properly and wisely decide when distributions to beneficiaries are appropriate. Trusts can help protect assets from your beneficiaries’ creditors (including claims arising in a beneficiary’s divorce) and can help preserve the value of the assets for future generations. - Use “grantor” trusts.

The most efficient planning, from a wealth transfer perspective to save on estate tax, is to use a so-called grantor trust. This trust is structured to treat you — the donor (the “grantor” of the trust) — as the owner for income tax purposes but not for gift or estate tax purposes. This means that the grantor will pay the federal income taxes attributable to the trust income, thus allowing the trust assets to grow much faster. The grantor’s payment of the trust’s income taxes is not treated as an additional gift to the trust.

The grantor also can sell assets to the trust in return for a low-interest promissory note. The sale of such assets will not cause the grantor to realize gain for income tax purposes, because the grantor is treated as still owning the assets for income tax purposes. If the combined income and appreciation of the assets sold to the trust exceeds the low interest rate on the promissory note, the excess can result in substantial growth for the trust. - Consider trusts that help multiple generations.

If the generation-skipping transfer (GST) tax exemption is also allocated to the trust, the trust can continue for multiple generations, with no estate or GST taxes due at the deaths of the beneficiaries. This is sometimes referred to as a “GST-exempt dynasty trust.” - Explore defined value transfers for hard-to-value assets.

Additional consideration is needed if the assets used to make the gifts are subject to valuation uncertainties (such as interests in entities that are not sold on public markets, or closely held entities).

Hard-to-value assets need to be appraised by a qualified appraiser and this appraised value will be reported on the donor’s gift tax return. If the IRS asserts that the assets are worth more than was reported on the gift tax return, payments of gift taxes may be required if the donor made gifts using most of his/her available exclusion amount.

To minimize the risk of valuation uncertainty, consider whether a formula gift is appropriate. Consult with your attorney about the possibility of making a formula transfer of that percentage of ABC Entity equal to $X million, as finally determined for federal gift tax purposes, or, rather than a specified dollar amount, equal to your remaining gift tax exclusion amount.

With a formula gift, if the IRS succeeds in maintaining that the price per share is higher than was reported on your gift tax return, the number of shares transferred would automatically adjust, but would still not exceed the specified dollar amount. Hopefully, that would result in no current gift tax payments. However, be aware that, while some court cases have recognized these types of formula transfers, the IRS has not officially sanctioned formula clauses. - Emphasize flexibility.

Gifts of the “bonus exclusion amount” (particularly if combined with subsequent sales to the grantor trust) could result in a very large trust. You may want to think through various alternatives so that you create a great deal of flexibility for those who administer the trust.

Possibilities include:

- Providing broad distribution standards with independent trustees, including methods for adjusting who serves as trustee

- Using an independent trustee (who can exercise broad discretion in making distributions)

- Providing other persons who would serve as investment or distribution directors, including nontaxable powers of appointment (giving the beneficiaries or other persons the power to “appoint” assets to other beneficiaries or other trusts)

- Giving the grantor or other persons the power to acquire trust assets by substituting other property of an equivalent value

- Giving special modification powers to so-called “trust protectors”

- Consider the basis adjustment.

Assets given to the trust would no longer be owned by the donor at death, so they would not be entitled to a “step up” in basis at the donor’s death. Consider this loss of basis step up at death before making large gifts of highly appreciated assets. - Look into allocating your GST exemption to existing GST non-exempt trusts.

Even if you do not want to make gifts to use the “bonus exclusion amount,” consider allocating your unused “GST exemption” (which may also be reduced from about $14 million to about $7 million at some point) to any trusts you’ve previously created that are not fully GST exempt. - Consider this opportunity to equalize prior gifts.

If you have made more gifts to some children and grandchildren than others, the “bonus exclusion amount” gives you the opportunity to equalize gifts, as desired. - Consider forgiving loans made to family members.

If you have any loan receivables, you can consider forgiving those outstanding loans that would result in a gift to which the “bonus exclusion amount” could apply.

Similarly, you could make a loan now of $14 million to family members (preferably to a grantor trust). Later, you could decide to forgive some or all of that loan, which would be treated as a gift at the time of forgiveness. This approach would be another way to structure a plan that would allow you to act quickly on a gift if it appears that the exclusion amount will be reduced. If you decide not to make a gift, the trust could repay the loan and the only cost to the trust would be the amount of interest owed on the short-term loan.

Ask for Help

Clearly, estate planning can get complicated very quickly. But the goal is very simple: to thoughtfully and strategically construct a plan that takes care of you and your family. Your Bessemer advisor is available to work closely with you and your estate planning attorneys to help you do that well.

- These exclusion amounts will continue to increase with inflation adjustments; but, for simplicity, we will assume they are $14 million for 2025 and $7 million for 2026.

- The exact amount you would be allowed to gift tax-free depends on how much of your lifetime exclusion amount you’ve already used.

This material is for your general information. It does not take into account the particular investment objectives, financial situation, or needs of individual clients. This material is based upon information obtained from various sources that Bessemer Trust believes to be reliable, but Bessemer makes no representation or warranty with respect to the accuracy or completeness of such information. The views expressed herein do not constitute legal or tax advice; are current only as of the date indicated; and are subject to change without notice. Forecasts may not be realized due to a variety of factors, including changes in economic growth, corporate profitability, geopolitical conditions, and inflation. Bessemer Trust or its clients may have investments in the securities discussed herein, and this material does not constitute an investment recommendation by Bessemer Trust or an offering of such securities, and our view of these holdings may change at any time based on stock price movements, new research conclusions, or changes in risk preference.