Family Foundations:

Thriving Through Times of Transition

- Private foundations are a popular and effective vehicle for giving families, and their numbers continue to grow, more than doubling in the past 30 years.

- While a foundation can be a great way to create a lasting charitable legacy, over time, inevitable leadership and other transitions can create challenges that obscure the way forward.

- In this A Closer Look, we examine three common transitions foundation boards navigate, the challenges they’ve encountered, and the ways Bessemer’s philanthropic advisory specialists were able to draw on their experience and expertise to devise solutions.

- While we focus on foundations specifically, many of the issues we explore also have applications for clients who use other types of giving vehicles, such as donor-advised funds.

Private foundations continue to be a popular vehicle for giving families. In fact, since the mid-1990s, the number of private foundations has more than doubled.1 At Bessemer Trust, we support hundreds of family foundations, often partnering with families from the outset by helping them establish the vision and structure for long-term success.

In other instances, we begin working with families whose foundations are already in midlife and facing a critical inflection point. The leaders of these well-established foundations usually share a deep desire to perform well in their roles, respecting and honoring the foundation’s legacy while ensuring the foundation remains relevant and responsive to the communities it serves. New leaders may be energized by the potential to explore new directions, shore up operational gaps, and create an inclusive and collaborative environment through which to engage the broader family.

However, the longer a foundation is in existence (two or three generations, and beyond), the more complex and difficult these transitions become,2 putting strains on family relationships and adding stress for those serving in board leadership.

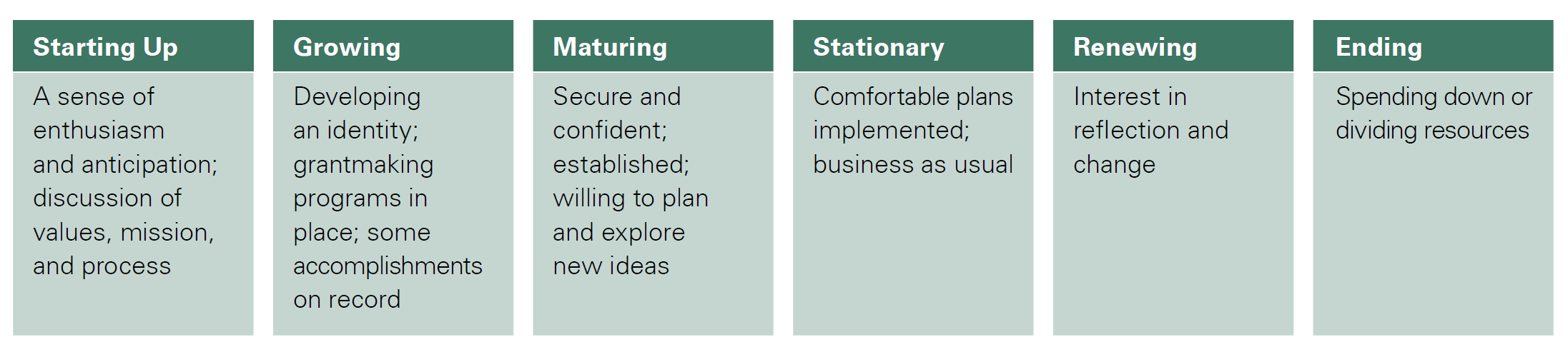

Family foundations, like other family enterprises, move through a distinct life cycle. From the early excitement of the launch, through growth and maturity, stability, or winding down or dividing resources, each phase brings challenges and opportunities. The transition from one phase to the next is often triggered by events within the family system, such as deaths/births, marriage/divorce, retirements/sales of the family business, and geographic dispersion. The foundation itself can also experience organizational shifts, such as an influx of assets, evolution in mission, structural changes, and board/staff leadership transitions.3

Often there is not a clear roadmap for managing through change, which can cause ambiguity and uncertainty for those in leadership roles. Family foundation board leaders may find themselves navigating one or more of these transitions simultaneously, which can prompt the need for reflection on why philanthropy continues to be a priority and a reexamination of how best to fulfill the family’s mission and goals.

In this A Closer Look, we examine three common transitions our clients experience: board leadership transition, influx of assets, and evolution in mission. The following case studies are hypothetical, but they are based on actual scenarios we’ve seen foundation boards navigate, the challenges they’ve faced, and how Bessemer drew from its expertise to devise solutions. Importantly, while our focus is foundations, many of the issues we explore also have applications for clients who use other types of giving vehicles, such as donor-advised funds.

Exhibit 1: The Stages of a Family Foundation Life Cycle

Exhibit 1: The Stages of a Family Foundation Life Cycle 1. Starting Up - A sense of enthusiasm and anticipation; discussion of values, mission, and process; 2. Growing - Developing an identity; grantmaking programs in place; some accomplishments on record; 3. Maturing - Secure and confident; established; willing to plan and explore new ideas; 4. Stationary - Comfortable plans implemented; business as usual; 5. Renewing - Interest in reflection and change; 6. Ending - Spending down or dividing resources;

Case 1: From the Kitchen Table to the Board Room Table

After selling the prosperous business they had built together, high school sweethearts Robert and Anna decided to devote more of their time to philanthropy. Within a few years, they had started a family foundation to support education, healthcare, and social services for low-income communities in the midwestern city where they were both raised in modest circumstances; in Florida, where they then lived; and in France, where they had been stationed early in their careers.

While raising their three children amid plenty, the couple spoke often of their own experiences growing up, of their parents’ struggles to provide on meager incomes, and of the importance of helping those less fortunate. While still young, the children were encouraged to donate part of their allowances and volunteer for charities the foundation supported. As teenagers and young adults, they were asked to explore and recommend potential new charities. Yet as the kids developed their own careers and started families, collective engagement in the foundation grew more difficult. Besides, Robert and Anna made most of their decisions on walks or at the dinner table and assumed their kids would one day carry on with the same informal collegiality.

The challenge. In their early 80s, without warning and in quick succession, Anna developed a fatal illness and Robert suffered an incapacitating stroke. At a time of grief, the grown children suddenly found themselves running a foundation they deeply wanted to maintain, both as their parents’ legacy and because they believed in doing so. Yet while the bylaws spelled out a clear mission to continue serving communities in the three chosen regions, they lacked a formal governance framework.

Despite generally cordial and warm relationships, strains began to show as the new directors grappled over board member responsibilities, who would lead and for how long, and even over regular expenses. Was one member’s fact-finding mission to France a legitimate foundation cost or a thinly disguised wine tour? Amid the growing weight of administrative and operational responsibilities and a fear of not fulfilling their parents’ legacy, the foundation directors turned to Bessemer for help.

Finding solutions. Bessemer’s philanthropic team recommended some immediate changes. First, they helped establish a regular cadence for board meetings, with formalized agendas, including discussion and voting procedures that helped elect one of the siblings as president. They coached her on managing formal meetings and ensuring that all voices were heard.

The Bessemer team shared best practices for governance and made recommendations for updating the bylaws to include qualifications for service such as age, relationship to the founders and/or prior nonprofit volunteer or board service. Through a collaborative process, the team helped the board develop a document outlining member roles and responsibilities. In consultation with their attorney and with coaching from the Bessemer team, they instituted travel and expense guidelines and a conflict of interest policy and process. To ensure the board would evolve over time to include new and more diverse perspectives, they established processes for expanding the board with extended family members and, potentially, external experts. And they established officer role descriptions and a schedule for rotating positions, including president.

Finally, with family members living in far-flung locations, the board launched its first coordinated online communications, including a software system for managing grants, shared files, and an easy-to-navigate portal for board members. The new tools and operational framework gave the foundation the structure it needed to thrive.

Which Governance Policies Should Foundations Adopt?

While specific policies will vary depending on a foundation’s size and purpose, governance covers areas such as:

- Mission and vision, including a mission statement and donor intent letter.

- Grantmaking guidelines, including annual budget projections, board-directed giving policies, and a grants committee charter.

- Board policies, including describing roles for board chair, CEO, and members, compensation and succession policies, and a junior advisory board charter.

- General policies, including investment and spending, conflicts of interest and whistleblowers, and travel and expense reimbursement.

- Long-term planning, including a strategic plan, organizational chart, and staff job descriptions.

Case 2: Navigating an Influx of Assets

A family foundation in the Southeast had for nearly two decades reflected the diverse passions of its founders, Michael and Carmen. During the time the couple was running the foundation, their areas of support ranged from American folk art to disaster relief to cancer research and more.

Michael and Carmen raised four children with similarly varied interests. The couple envisioned the foundation continuing its multifaceted journey in perpetuity and arranged to leave a substantial financial legacy as part of their estate. They trusted that a second generation of board members, led by their adult children and supported by nieces and nephews, would carry on when the need arose.

The challenge. The assets the couple left created opportunities for the foundation to expand and deepen its impact. Yet because the bequests ranged from concentrated stock positions to equity in the family business, real estate, and art, the foundation’s second-generation leaders had to spend considerable time and effort managing the influx to create a steady, reliable stream of capital for grants.

They also weren’t sure how to leverage the increased grant funding most effectively. In addition to the previous areas of support identified by their parents, the new leaders had their own interests. One sister, a physician, envisioned the foundation becoming a force in mental health. A brother had a strong interest in combatting climate change, and the other siblings were passionate about education and affordable housing, among other causes.

Should they increase their funding to current grant recipients to honor their parents’ legacy? Should they wind down those commitments and transition to new areas of support to reflect their own interests? Or should they combine those options — keeping some of the “legacy” grantees while also expanding into new areas?

Exploring solutions. When Bessemer began working with the second generation, the board asked for help in organizing the foundation’s newfound wealth.

Bessemer specialists helped create a plan for unwinding some of those concentrated, illiquid assets, as well as implementing a formal investment policy statement (IPS) describing what the foundation aimed to achieve through its investments. Among the objectives outlined in the IPS were to preserve and grow the corpus while generating steady income for grantmaking purposes.

In addition to providing expertise on investment matters, Bessemer was able to assist with their approach to the grantmaking. Bessemer specialists conducted a facilitator exercise with the new foundation members to sort through and prioritize potential areas of foundation support. Given the many current grantees and the new members’ own diverse interests, they also considered the optimal number of causes to support to avoid spreading their giving among too many recipients and thereby diminishing chances for making a significant impact.

In the end, they decided to maintain several of the foundation’s legacy grant commitments and also add two new areas to support: climate change and mental health. As noted above, these were areas of special interest to two of the members, but they also saw potential tie-ins to areas of interest for other members — education and affordable housing, since education can play a pivotal role in combatting climate change and the connection between mental health and experiencing homelessness has long been established.

This exercise served as a starting point for developing a mission statement for the foundation as well as a formal spending policy that specified how and when funds would be distributed. This included provisions for continuing to support several of the parents’ legacy grants as well as for supporting new board-directed grants and responsive grants to answer urgent community needs in the wake of disasters or other emergencies.

With an eye toward the future, the board appointed Bessemer to serve as successor corporate trustee once a majority of the board was represented by the third generation. In the meantime, current foundation leaders earmarked funding for the third generation to recommend their own grants while gaining exposure to foundation governance and operations.

A Mission Statement Should:

- Reflect shared values

- Declare a common purpose and goals

- Explain the foundation’s work to potential grantees

- Be comprehensive yet focused enough to provide direction

- Provide a framework for making decisions

Case 3: Refreshing the Mission and Focus

A New York-based family foundation, formed in the late 1960s from inherited wealth, had for decades supported social and environmental causes in New York, the United States, and globally. Along the way, it earned a place among the most venerable and highly regarded organizations of its kind in the country. Nearly 200 charitable organizations counted on the foundation for regular grants ranging from a few thousand to several hundred thousand dollars a year. Essential to the foundation’s longevity were rock-solid policies on governance, investments, and spending that helped ensure steady management and financial health across generations.

The challenge. After a decade of the second and third generations serving as board members, the very traditions that gave the foundation its strength and stability had in some ways become a liability. To them, the foundation’s mission and roster of charities had ossified. With so many longstanding recipients, the board had little or no sense of what, specifically, the grants were being used for, and what impact they were having on the communities served.

They wondered whether, by supporting the same organizations year in and year out, the foundation was truly keeping step with community needs. And while deeply cognizant of the need to maintain and honor the founders’ legacy, they worried that their own tenure on the board might largely amount to “rubber-stamping” existing grants to existing recipients. As a board, they desired to narrow the list of recipients, better understand the impact of the grants, and more carefully define the foundation’s priorities. But where to begin?

Finding solutions. Before moving forward, the board members needed a clearer sense of the scope of existing grant commitments. They consulted Bessemer experts, who recommended they conduct a forensic analysis of the foundation’s grantmaking history for 10 years prior to the passing of the founding generation. This included the history and mission of each recipient, the amount of the grants, and how the funds were used. Next, Bessemer surveyed the current board to better understand members’ personal interests and their impressions of what had worked well in the past, and what might need to be changed.

Bessemer used these analyses as the basis for recommendations to be enacted over the next two years, determining which existing grants to maintain, which to “tie off,” and potential new areas and organizations to explore. During a formal strategy session, the board discussed the findings and recommendations and considered its options.

The members decided to narrow the recipient list by focusing on three core funding areas: hunger and food insecurity, access to quality healthcare, and criminal justice. For the organizations that no longer aligned with the new direction, the board set a careful, responsible process for phasing out donations, so as not to harm the relationship with and financial health of longtime recipients. As these new processes unfolded, the board reenergized the foundation and set a course for long-term sustainability.

Setting Your Own Course

If you’ve recently found yourself helping guide a family foundation through a time of transition, your own experience may be similar to one of these cases or a combination of them. Whatever the situation, the important thing to remember is that you’re by no means alone. The stresses and growing pains are a natural part of the life cycle of your foundation.

While you may at first feel overwhelmed with the task ahead, keep in mind that roadmaps do exist. Good governance processes and operational frameworks, once in place, can help codify the new direction and support positive and meaningful family dynamics. Bessemer Trust is here to serve as a strategic advisor and partner to help navigate these inflection points. We’ve seen and helped many foundations and families endure transitions and emerge on the other side stronger than before, with an even clearer sense of how to have a positive impact on the world.

Resources

Our Recent Insights

- “A Closer Look: Family Dynamics and Philanthropy”

- “Finding Your Voice as a Next Gen Philanthropist”

- Sharing Your Vision and Values: Exploring Letters of Wishes

- The Life Cycle of an Estate: Preparing Your Family for the Estate Administration Process

Reports and Articles

- 10 Things Every New Foundation Board Member Should Know by the Council on Foundations

- “Building the Board Your Foundation Deserves: The Governance Checklist,” by the National Center for Family Philanthropy

- Private Foundation Governance & Tax Guide by PKF O’Connor Davies

Philanthropy Networks & Peer Learning Communities

- National Center for Family Philanthropy, thought leader and community of family funders

- Exponent Philanthropy, national network of foundations with few or no staff

- The Philanthropy Workshop, global network of philanthropic leaders

- Nexus, community of next gen philanthropists

- https://johnsoncenter.org/blog/philanthropy-1992-2022-budgets-swelled-and-certain-nonprofit-types-flourished/

- Generations of Giving: Leadership and Continuity in Family Foundation (Gersick, 2006).

- 3 Family Philanthropy Transitions: Possibilities, Problems and Potential, National Center for Family Philanthropy, 2015.

This material for your general information. The discussion of any estate planning alternatives and other observations herein are not intended as legal or tax advice and do not take into account the particular estate planning objectives, financial situation or needs of individual clients. This material is based upon information obtained from various sources that Bessemer believes to be reliable, but Bessemer makes no representation or warranty with respect to the accuracy or completeness of such information. Views expressed herein are current only as of the date indicated and are subject to change without notice. Forecasts may not be realized due to a variety of factors, including changes in law, regulation, interest rates, and inflation.